While the new Dutch Trade and Development policy sets strong trade objectives, it shows little ambition regarding responsible business conduct. Although the Dutch like to see themselves as frontrunners on the issue of responsible business conduct, the government’s multi-stakeholder agreements policy has so far yielded only limited results. Meanwhile, the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Law seems to have stalled in the Senate.

Photo: Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, Flickr, CC (edited)

Photo: Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, Flickr, CC (edited)The new Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation policy note centres around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and promoting trade and investment for Dutch companies, in line with the government’s ambition to increase the share of exports in the Dutch GDP to 40% by 2030 (up from 32% in 2013). The policy almost exclusively focuses on potential positive contributions of companies to sustainable development, thereby ignoring the various ways in which companies can also have a harmful impact on human rights and the environment. It also emphasises the opportunities for companies “to make money out of the SDGs” [sic]. Responsible Business Conduct and corporate accountability issues are addressed only briefly in the new Trade & Aid policy, which was presented by Minister Sigrid Kaag in May 2018. Minister Kaag took office in October 2017 as part of the new four-party government coalition, led by Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

Update: In a recent letter (see here, Dutch only), Minister Kaag endorsed the ambition of her predecessor Ploumen: 90% of the large companies in the Netherlands, should explicitly endorse the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in their international activities. In addition, Minister Kaag announced a deadline: this ambition should be realized in 2023 and progress will be monitored in 2018 and 2020.

Structural delays in responsible business agreements process

Trade and Development Minister Kaag will continue the responsible business conduct agreements (‘covenants’) policy for at least another two years. This policy, which was developed by her predecessor Lilianne Ploumen, aims to develop multi-stakeholder agreements between the government, companies, and civil society organisations in order to address social and environmental issues in 13 ‘high-risk sectors’. So far, two sector wide agreements (on banking Due to its large scope and participation of most major banks in the Netherlands, the banking agreement is considered sector wide. and textiles/garments) and three sub-sector agreements (vegetable proteins, forestry, and gold) have been developed. The new Trade & Aid policy announces the completion of another four agreements before the summer of 2018, while negotiation processes for four other sectors are still ongoing. The government also intends to start negotiations on new sector agreements and aims to increase participation from companies. The agreements should also address the issue of living income more prominently, according to the new policy note.

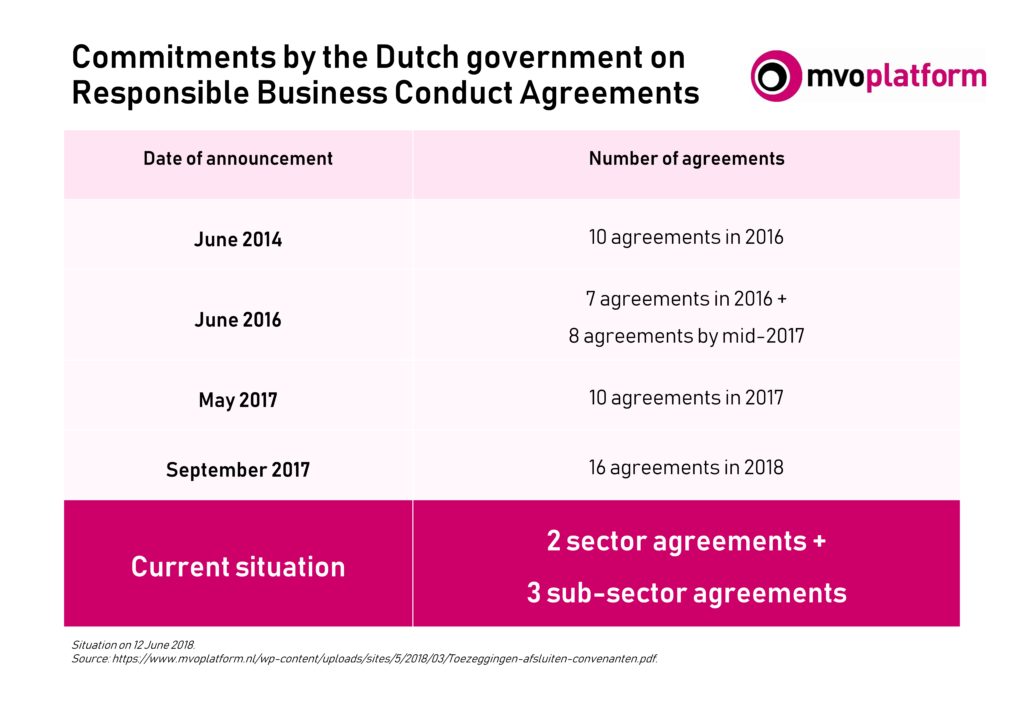

Yet an analysis of the outcomes of the responsible business agreements policy so far shows that the development of these agreements is structurally and severely delayed. This analysis, which was done by the MVO Platform in March 2018, also highlights the incomplete and irregular ways through which the government provides information on progress, policy objectives, and challenges of the responsible business conduct agreements policy. The initial goal of concluding 10 sector agreements by the end of 2016 has still not been met. Several new targets have been announced since then (most recently the completion of 16 agreements by the end of 2018), but so far the government has never even been close to meeting these objectives. There have been no serious negotiations on sector wide responsible business agreements in eight risk sectors: the chemical industry, construction, energy, metal, electronics, oil and gas, retail, and wholesale. The expected completion dates of agreements in other sectors are continuously postponed. For example, the government has announced no less than seven different dates for the completion of the responsible business agreement for the natural stone industry. Yet none of these timelines has been met.

Low market shares and quality of agreements

The participation of companies in the agreements has turned out to be a key issue. Although the banking and garment agreements have been signed by a substantial number of companies in terms of market shares, the sub-sector agreements only cover less than one percent of the total number of companies operating in the respective risk sectors. There is no direct participation from companies in several sector agreements, some of which are currently still under negotiation. Instead, industry associations participate on their behalf and as such it is unclear to what extent individual companies actually commit to the sector agreements. There so far have been no individual commitments from companies in eight of the thirteen risk sectors. In terms of quality, some agreements do not sufficiently address the topic of implementing due diligence at the company level, despite this being the main aim of the policy.

An evaluation of the responsible business agreements policy will be undertaken in 2019, after which the government will assess whether more binding measures are required. The MVO Platform believes that binding measures are required in addition to self-regulation (such as the sector agreements), as voluntary initiatives have not led to a sufficient level of implementation of the UN Guiding Principles and the OECD Guidelines. Legislation can also reinforce these voluntary initiatives by addressing the issue of freeriders and ‘last movers’. Minister Kaag has adopted a rather hesitant position on legislation and has indicated that no further steps will be taken until the upcoming evaluation of the responsible business agreements policy has been completed. This means that binding measures for companies, if any, will probably only be developed after the next general elections in 2021.

Impasse on Child Labour Bill

Meanwhile, the Child Labour Due Diligence Bill seems to have stalled in the Dutch Senate. The law proposal, which was passed by the House of Representatives in February 2017, requires companies to conduct due diligence on child labour risks in their supply chains and to develop action plans if necessary. When the Child Labour Bill was debated by the Senate in December 2017, however, several Senators proved to be sceptical of its effectiveness, monitoring mechanisms, and level of detail and Minister Kaag seemed to support many of these critiques. The Labour Party, which had initiated the bill, managed to postpone the vote in an attempt to save the bill from direct rejection by the Senate. Yet six months after the debate, it remains unclear what solutions are being developed in response to these critiques, when the process will continue, and whether the Senate will ultimately pass the bill.

The Dutch in international perspective

Although the Dutch government considers their responsible business conduct policies as one of the most progressive in the world, a recent report that was commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs paints a more nuanced picture. The EU as well as the governments of France, the UK, Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands each use different instruments to promote responsible business conduct, including legislation, sectoral guidelines, and voluntary initiatives. The effectiveness of most instruments (including the Dutch responsible business agreements policy) remains largely unproven. Other countries are ahead of the Netherlands in certain regards, such as legislation (e.g. France and the UK), clear communication to companies (e.g. Switzerland and Germany), the inter-ministerial coordination of responsible business policies (e.g. Germany), and organised stakeholder dialogue (e.g. France and Germany).

All in all, the Dutch government’s emphasis on promoting trade and narrow focus on the potentially positive contributions of companies to sustainable development might further reduce the importance of responsible business conduct policies. In addition, it seems unlikely that the Senate will pass the Child Labour Due Diligence Law anytime soon. The government continues to focus on the voluntary responsible business conduct agreements as the main policy instrument to promote the implementation of the OECD Guidelines and UN Guiding Principles by companies. Yet after years of slow progress and limited participation of companies in the existing sector agreements, it remains to be seen whether this instrument will lead to the implementation of due diligence by substantial numbers of companies. Overall, other policy goals of the Dutch government seem to be prioritised above enforcing responsible business conduct.